Prelude to The Right to Abstain:

“So we must go out to him outside the camp, bearing his reproach. For here we do not have a permanent city, but we seek the city that is to come.” –Hebrews 13:13–14

Democracy is a fascinating thing, especially in the context of a Constitutional Republic. What “American democracy” has become is even more curious. This hybrid has bred a mindset among its citizenry that, oddly enough, is antithetical to its essence.

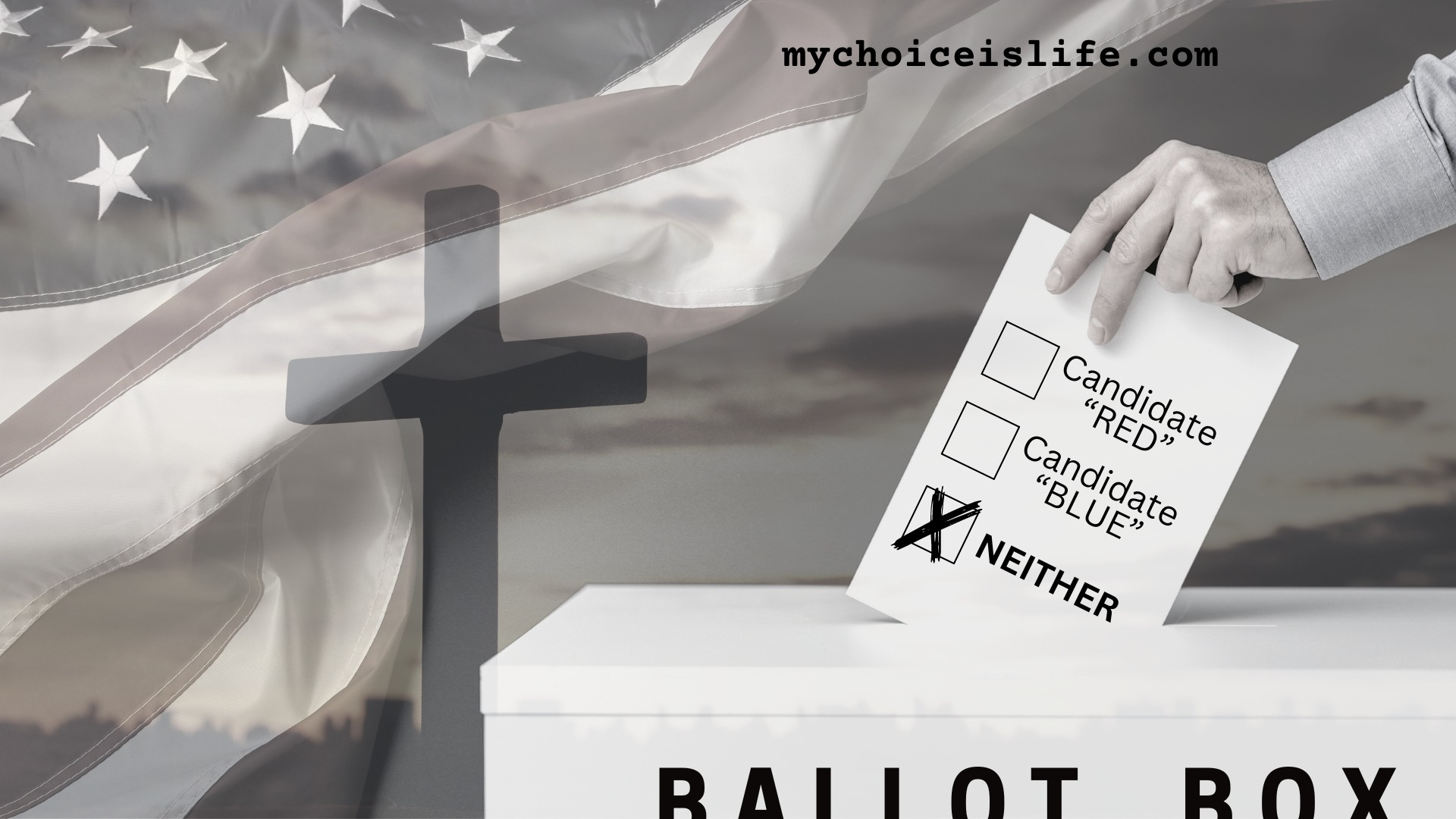

Put simply, democracy is government by the people, wherein the people’s governance is expressed via elected representation. So far, so good. What has happened in the U.S., however, is the whittling down of representative options, essentially leaving a two party system. Although there may be outliers on nearly every ballot, by and large, elections end up being between the two major party’s representatives. What the devolution to this Binary Electoral System (or B.E.S. as it will be referred to in what follows) has caused, is the oversimplification of the vote. Here’s what I mean by that.

Most people, rather than thinking of it as voting for a Red or Blue candidate (that stands for or against a wide array of issues), actually think —with the help of the Media— that the choice they are making is really between Right or Wrong, Up or Down, Good or Evil. It is almost as if a B.E.S., such as the American political machine, is engineered to elicit this type of oversimplification and binary decision-making.

While I will say that there are times when the choice is between those stated above, more often than not, it is between the “lesser of two evils.” So often, in fact, that it has become a common defense of one’s preferred candidate: “Well, they’re not perfect, but the other one is worse.” The only problem with that logic is that, when a choice is made between the lesser of two evils, evil is still elected.

What to do about this?

Abstention: A Brief Overview of Motivating Factors

In a democracy (even a constitutional republic that has become one), there is a third option. When the B.E.S. presents the selected options and they are both undesirable, rather than choose the lesser, the individual can choose not to cast their vote at all. This is called abstention. There are two main causes, according to scholars, that drive abstention. One is indifference. The other is alienation. Grant M. Hayden, Professor of Law at SMU-Dedman School of Law, describes the latter in his paper on Abstention this way:

“The second major cause of abstention [is] voter alienation. Alienated voters, however, abstain not because they are indifferent, but because the slated candidates are too far away from their ideal point. For an alienated voter, there may be instrumental benefit to the election of a particular candidate, and thus such a voter is not necessarily indifferent. But this benefit is outweighed in the equation by the value of protesting against a political system that offers such lousy choices. This value may be alternatively described as a noninstrumental benefit of abstaining (the satisfaction of registering your dissatisfaction) or a cost of voting (losing out on that benefit).

Alienated voters may abstain in different ways. In many cases, they may simply fail to show up at the polls on election day. In countries with compulsory voting, such a failure is obviously a more potent method of registering dissatisfaction, and hence such protest abstention has been observed and studied in places such as Brazil and the former USSR. Alienated voters may also make their intentions clear by actually showing up at the polls and casting a protest vote. In some jurisdictions, even in the United States, the official ballot contains a “None of the Above” option. In other places, voters may intentionally nullify their ballots by writing in the same sentiment, writing in the name of a cartoon character, or drawing an X through the ballot. The protest may be that of a single individual or of a more organized campaign, as in the recent “Voto Nulo” campaign in Mexico’s recent midterm elections. In any case, abstention is a way to express dissatisfaction with the slated candidates or, in some cases, the entire political system.”

—Prof. Grant M. Hayden “Abstention: The Unexpected Power of Withholding Your Vote”

Most people who vie for this option, either for the sake of indifference or alienation, receive a great deal of flack for it. In what remains, I would like to reverse-engineer the act of abstention theologically from a place of alienation, and address the “flack” that inevitably ensues from making this choice. There’s quite a bit more to unpack here than it seems.

Reverse-Engineering Abstention

To begin the process of reverse-engineering abstention, it is important to understand why people vote rather than abstain, and why abstention is generally met with a negative response. As to why most people vote, Prof. Hayden offers a brief explanation below:

“Most of the work done in answering the question why voters abstain comes out of the theoretical framework of rational choice theory. Anthony Downs, in his classic work, An Economic Theory of Democracy, set the stage by describing the individual decision to vote or abstain in terms of an expected utility calculation. Downs’s formula thus promised to give social scientists a useful tool to explain and predict voting behavior.

This formula, though, immediately gave rise to an issue regarding voter turnout. But it wasn’t the more familiar issue of explaining low (and falling) voter turnout, but its opposite —why people bother to vote at all. In most applications of the formula, especially in large elections, the probability of casting the deciding vote is infinitesimally small. The basic formula, then, predicts that most instrumentally rational people will rarely, if ever, take the time to vote. This is, of course, at odds with the fact that millions of people regularly show up at the polls. Thus, the issue of voter turnout was that far too many people vote than can be explained by Downs’s formula. This led to much consternation in the rational choice field, eventually leading Bernard Grofman to pose the question whether turnout was the “paradox that ate rational choice theory.”

The fact that people vote in large numbers either meant that many people were acting irrationally or that there was something wrong with the formula. Suspecting the latter, William Riker and Peter Ordeshook reworked the formula into its present form by adding a term intended to capture the benefits to voting unrelated to being decisive to the outcome. The noninstrumental benefits of voting captured include such things as “the satisfaction from compliance with the ethic of voting…affirming allegiance to the political system…affirming a partisan preference…and other benefits sometimes described as fulfilling a “sense of citizen duty”‘ (or, less formally, as getting “a big bang out of pulling the lever”).’ The noninstrumental parts of the equation appear to drive most decisions to vote…”

—Prof. Grant M. Hayden “Abstention: The Unexpected Power of Withholding Your Vote”

To summarize, the reasons that compel the average individual to vote have less to do with the outcome which voting produces, and more to do with the act of voting itself, along with the benefits received from performing said act. Fascinating. Most Americans vote, even if they do not prefer either candidate, for one of the reasons stated above in bold, or something similar. Voting, in the majority of cases, is essentially driven by a dopamine hit en masse that is capped off by being allowed to wear an “I Voted” sticker for the remainder of the day. It’s no wonder then, that when an individual elects abstention and makes this choice known, the common responses are as follows:

“You need to vote. It’s part of being an American.”

“You should make your voice heard.”

“Voting is an important part of democracy.”

Or, the one that is most pertinent to our discussion and slightly accusatory:

“If you don’t vote for *fill in the blank* then you’re giving a vote to *fill in the blank*,” or words to that effect.

I’m not sure about the math on that last one. Professor Hayden fully breaks down why that assumption is misguided in his paper, but for our purposes, let’s look theologically at what this type of statement reveals about those who make it.

Implications

There are three major implications present in this statement. Two are dependent upon theological preferences. The other is implicit to the statement, regardless of the declarant’s theological lean. I’ll explain the dependent implications first.

Like it or not, the debate over “Free Will” and “God’s Sovereignty” comes into play in most theological discussions. I assume this because, ontologically speaking, those are the only two options. In regard to abstention, however, neither one helps the case against it.

If the declarant believes in God’s Sovereignty: that God not only controls, but is the driving force behind every event in history —past, present, and future— and the course of every person’s life and eternal destiny has been predestined before they were born, then a response like the one in question is illogical. If abstention is selected by an individual, then they were predestined to select it. Furthermore, following the logic of God’s Sovereignty stated above, the outcome of the event that the act of abstention potentially “affects” has already been predetermined as well. Any “choice” to abstain has no determinative impact on the outcome, as God in His sovereignty, causes events to unfold just as He has predestined. Thus, the declarant who adheres to an ontological view of Total Sovereignty nullifies any case they would make against abstention by their own theological leanings.

If the declarant adheres to a belief in Free Will or Free Choice, their parroting of the response in question implies a good deal more than even they may realize. For this type of individual to disagree with abstention, and to make the above accusatory claim, is for them to call their own bluff. The belief that a person is an agent of Free Will/Choice implies that what a person chooses to do or not do has an affect on the outcome of events, and therefore history. That is why one who believes this way is so insistent upon voting—and for their preferred candidate. Not to do so will have consequences. Oddly enough, it is this very same logic that invalidates the insistence.

If one must choose between the “lesser of two evils”, what is implicit to the acceptance of that premise is the unavoidable choice of some sort of evil. This position is worse than that of the Total Sovereignty side. It has the Free Will/Choice camp insisting that the election of evil is inevitable, perhaps even predetermined —the only true choice being of to which degree.

Irony abounds. On the one side, you have Total Sovereignty arguing that choosing abstention might negatively affect an already predetermined, and therefore fixed outcome, while Free Will claims that doing so will hand the win to the greater of the two inevitable evils.

However, what lies at the heart of this response, no matter the individual’s theology, is the inadvertent admittance that abstention is, of the three options, the most efficacious. It has real swaying power. Otherwise there would be no need to try and dissuade the abstainer from doing so.

Neither

Abstention is the choice not to assimilate to the B.E.S.. It’s the choice to agree with neither —to select a third option. It is this unwillingness to choose between two wings of the same bird, between the lesser of two evils, that gives it real and true authority—that makes it an actual choice.

The B.E.S. has already selected the options, so what it presents is only the illusion of real choice. By reducing the selection to two, the choice has already been made for the people. As either candidate A or candidate B will be elected, the voter has merely played the machine’s game. That is the genius of a binary system: limit the field of options and control the outcome. Fortunately for the citizenry of the United States, it is not yet illegal to abstain from voting, thereby, making it mandatory to participate in the B.E.S..

A system that limits choice is ultimately after control. A desire to control is driven by fear. That is the very heart of the issue with abstention: fear. It is a fear of those who won’t pledge allegiance to the political system or a partisan preference, who take no satisfaction in compliance with the ethic of voting or from fulfilling their “citizen duty.” It is a fear of those who won’t assimilate just so they can experience the noninstrumental benefits of voting for voting’s sake.

The reality is, when one willingly assimilates into a system, the system has the power. It holds all the cards; it sets the board and decides the rules. That’s how binary systems work: A or B? 1 or 2? Red or Blue? Abstention is a disengagement —a disconnection— from the B.E.S.. Abstention is a real choice. It requires looking at the lesser of two evils and calling them both what they are. It is a refusal to settle. And because the one who chooses neither goes against the grain (because of refusal to assimilate), the abstainer is led out into the exilic political wilderness, crying out with a loud voice, “God does not need evil to bring about His ends!”

One final thought: because of the B.E.S. programing and the mindset it has instilled in its allegiants, the accusatory response we have addressed is better phrased as a question:

“Are you with us or our political enemies?”

Our answer to that question, as we choose to wander the exilic wilderness of abstention and operate outside the confines of the political system, is simply: “Neither”

“And it happened, when Joshua was by Jericho, he looked up, and he saw a man standing opposite him with his sword drawn in his hand. And Joshua went to him and said, “Are you with us, or with our adversaries?” And he said, “Neither. I have come now as the commander of Yahweh’s army.” —Joshua 5:13–14a